Whither Mario Factory?: The Downside to Academic Publishing

I've been sitting on this material for a while. Many of my informants would recognize it as coming from back in 2006 when I was passing the PDFs around Vicarious Visions. Starting in 2008, the essay has been reviewed well and reviewed poorly and still not accepted. One interesting thing has been that despite good reviews it has even been rejected, told to go to something more "New Media" or "Game Studies." One of those notes came from a journal with "New Media" in its name, but I digress. So while I'll continue to push its publication through, the empirical material is simply too interesting to keep closed off from view as I await further feedback. Thus, some excerpts from an as-of-yet unpublished manuscript, "Whither Mario Factory?"

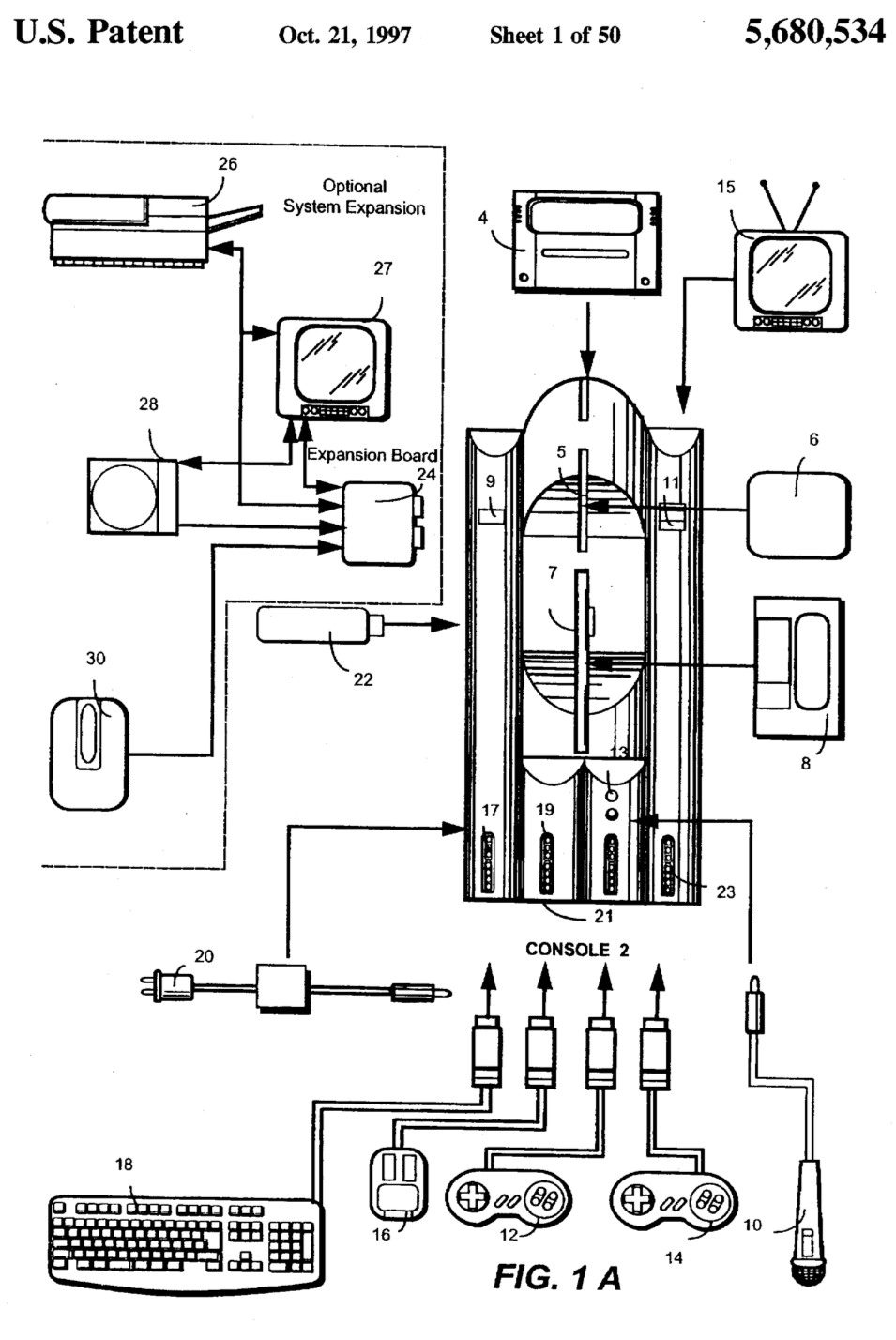

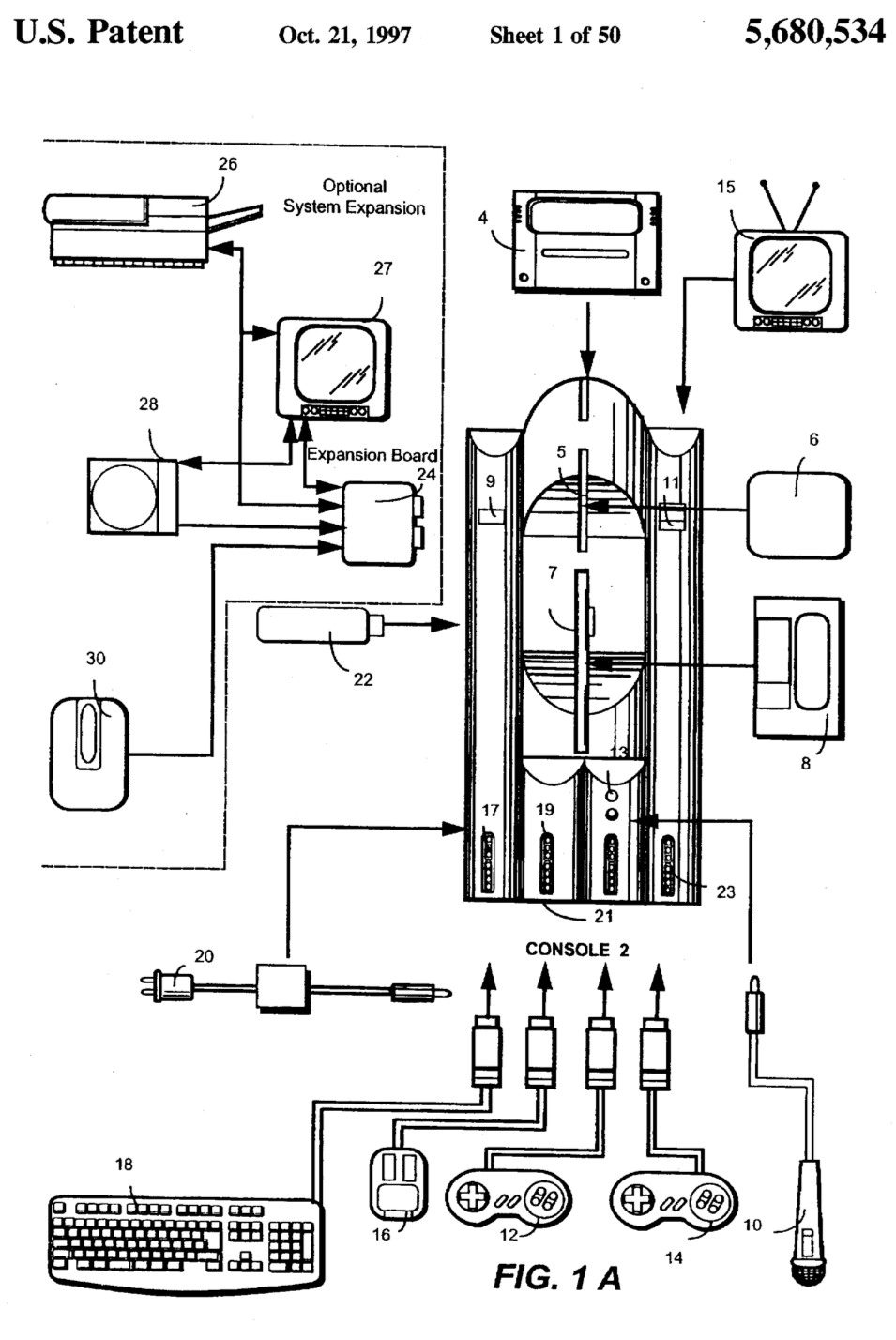

On Halloween of 1994 Nintendo filed for a series of patents that were later granted between the years 1997 and 2000. This essay refers to them more homogeneously as "Mario Factory" (Hibino and Yamato, 1994; Yamato et al., 1994a; Yamato et al., 1994b). This sequence of documents describe a videogame development, testing, and manufacturing system designed specifically for hobbyists and users to enjoy the creative possibilities of developing games for console videogame systems. Many of the systems and ideas described in the documents have not yet come to market for licensed Nintendo game developers and certainly not for the general player or hobbyist game developer.

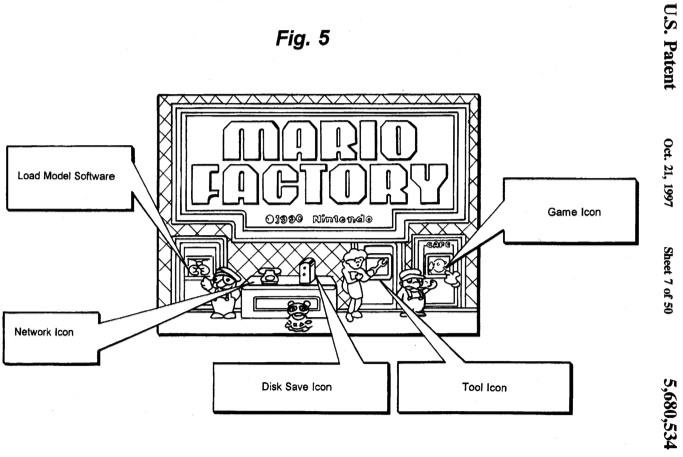

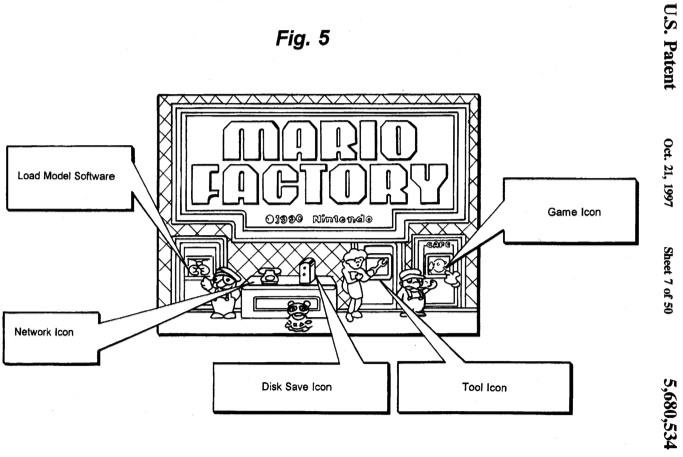

Mario Factory, at its core, was about creating, not only the possibility of (co)creative content creation for console video games, but an entire set of tools by which users could begin (co)creating games. Figure 1 depicts a splash screen from this hypothetical device. While the patent seems to specifically target less technically inclined would-be videogame developers, it was also stated that these same tools would prove as productive prototyping and testing systems for more experienced videogame developers.

As early as 1994, Nintendo was critically aware of the complexity associated with videogame development practices and the kinds of interdisciplinary creative collaborative practice that is necessary for success. While their patent hints at perhaps a declining collaboration between engineer, artist, and designer, it seems to be more about creating tools that foster effective collaborative practice between those groups.

Mario Factory was, in effect, a DevKit for the masses. This approach hints at a very different possibility than one that is currently experienced by game developers. DevKits were introduced so that game developers could create games for consoles where the hardware differed significantly from that of PC's. Nintendo developed technologies to bridge the gap between the PCs, where code was typically written, and the consoles, which ran the compiled code.

Hibino, T. & Yamato, S. (1994). U.S. Patent No. 5599231. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Assignee: Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Yamato, S. et al. (1994a) U.S. Patent No. 5680534. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Assignee: Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Yamato, S. et al. (1994b) U.S. Patent No. 6115036. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Assignee: Nintendo Co., Ltd.

On Halloween of 1994 Nintendo filed for a series of patents that were later granted between the years 1997 and 2000. This essay refers to them more homogeneously as "Mario Factory" (Hibino and Yamato, 1994; Yamato et al., 1994a; Yamato et al., 1994b). This sequence of documents describe a videogame development, testing, and manufacturing system designed specifically for hobbyists and users to enjoy the creative possibilities of developing games for console videogame systems. Many of the systems and ideas described in the documents have not yet come to market for licensed Nintendo game developers and certainly not for the general player or hobbyist game developer.

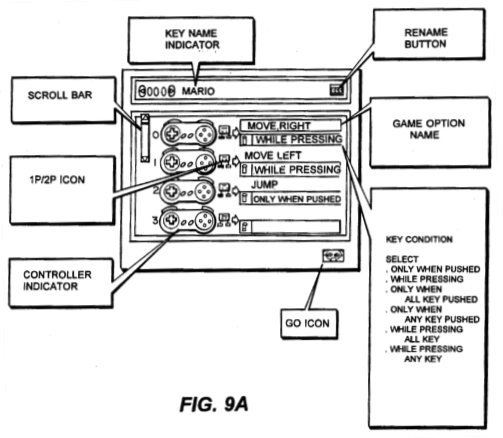

Mario Factory, at its core, was about creating, not only the possibility of (co)creative content creation for console video games, but an entire set of tools by which users could begin (co)creating games. Figure 1 depicts a splash screen from this hypothetical device. While the patent seems to specifically target less technically inclined would-be videogame developers, it was also stated that these same tools would prove as productive prototyping and testing systems for more experienced videogame developers.

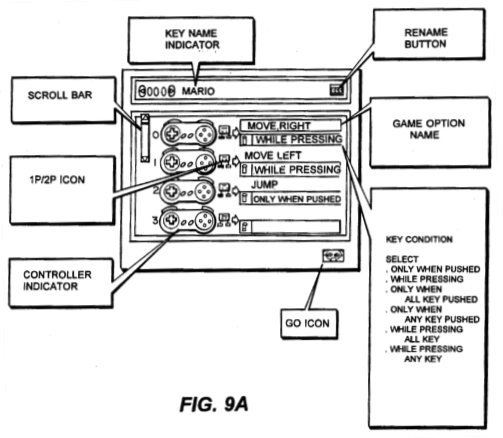

This invention relates generally to a method and apparatus for generating unique videographic computer programs. More particularly, the present invention relates to a video game fabricating system designed primarily for users who are unfamiliar with computer program[ing] or video game creating methodology. Such users may conveniently create a unique video game through and icon driven, interactive computing system that permits a video game to be executed, stopped, edited, and resumed from the point where the editing began with the editorial changes persisting through the remainder of game play.

...

In accordance with the present invention, unique video games may be simply created by users ranging from a relatively unsophisticated elementary school students to sophisticated game developers. A unique hardware and software platform enables users to create original games by selecting icons which access more detailed editor screens permitting the user to directly change a wide variety of game display characteristics concerning moving objects and game backgrounds. (Yamato et al., 1994a53)

As early as 1994, Nintendo was critically aware of the complexity associated with videogame development practices and the kinds of interdisciplinary creative collaborative practice that is necessary for success. While their patent hints at perhaps a declining collaboration between engineer, artist, and designer, it seems to be more about creating tools that foster effective collaborative practice between those groups.

Mario Factory was, in effect, a DevKit for the masses. This approach hints at a very different possibility than one that is currently experienced by game developers. DevKits were introduced so that game developers could create games for consoles where the hardware differed significantly from that of PC's. Nintendo developed technologies to bridge the gap between the PCs, where code was typically written, and the consoles, which ran the compiled code.

Hibino, T. & Yamato, S. (1994). U.S. Patent No. 5599231. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Assignee: Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Yamato, S. et al. (1994a) U.S. Patent No. 5680534. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Assignee: Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Yamato, S. et al. (1994b) U.S. Patent No. 6115036. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Assignee: Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Labels: DevKit, game development, Nintendo, Tools